A Day in the Life

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles that was released as the final track of their 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Credited to Lennon–McCartney, it was written mainly by John Lennon, with Paul McCartney contributing the song’s middle section. Lennon’s lyrics were inspired by contemporary newspaper articles, including a report on the death of Guinness heir Tara Browne. The recording includes two passages of orchestral glissandos that were partly improvised in the avant-garde style. As with the sustained piano chord that closes the song, the orchestral passages were added after the Beatles had recorded the main rhythm track.

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles that was released as the final track of their 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Credited to Lennon–McCartney, it was written mainly by John Lennon, with Paul McCartney contributing the song’s middle section. Lennon’s lyrics were inspired by contemporary newspaper articles, including a report on the death of Guinness heir Tara Browne. The recording includes two passages of orchestral glissandos that were partly improvised in the avant-garde style. As with the sustained piano chord that closes the song, the orchestral passages were added after the Beatles had recorded the main rhythm track.

A reputed drug reference in the line “I’d love to turn you on” resulted in the song initially being banned from broadcast by the BBC. Since its release on Sgt. Pepper, “A Day in the Life” has been issued as a B-side and also on various compilation albums. Jeff Beck, Barry Gibb and Phish are among the artists who have covered the song. Since 2008, McCartney has included the song in his live performances. It was ranked the 28th greatest song of all time by Rolling Stone. In another list, the magazine ranked it as the greatest Beatles song.

Lyrics

Tara Browne

According to Lennon, the inspiration for the first two verses was the death of Tara Browne, the 21-year-old heir to the Guinness fortune who had crashed his Lotus Elan on 18 December 1966 in Redcliffe Gardens, Earl’s Court. Browne had been a friend of Lennon and McCartney, and had, earlier in 1966, instigated McCartney’s first experience with LSD.

Lennon adapted the song’s verse lyrics from a story in the 17 January 1967 edition of the Daily Mail, which reported the ruling on a custody action over Browne’s two young children.

During a writing session at McCartney’s house in north London, Lennon and McCartney fine-tuned the lyrics, using an approach that author Howard Sounes likens to the cut-up technique popularized by William Burroughs. “I didn’t copy the accident,” Lennon said. “Tara didn’t blow his mind out, but it was in my mind when I was writing that verse. The details of the accident in the song—not noticing traffic lights and a crowd forming at the scene—were similarly part of the fiction.”

McCartney expounded on the subject: “The verse about the politician blowing his mind out in a car we wrote together. It has been attributed to Tara Browne, the Guinness heir, which I don’t believe is the case, certainly as we were writing it, I was not attributing it to Tara in my head. In John’s head it might have been. In my head I was imagining a politician bombed out on drugs who’d stopped at some traffic lights and didn’t notice that the lights had changed. The ‘blew his mind’ was purely a drugs reference, nothing to do with a car crash.”

“4,000 holes”

Lennon wrote the song’s final verse inspired by a Far & Near news brief, in the same 17 January edition of the Daily Mail that had inspired the first two verses. Under the headline “The holes in our roads”, the brief stated: “There are 4,000 holes in the road in Blackburn, Lancashire, or one twenty-sixth of a hole per person, according to a council survey. If Blackburn is typical, there are two million holes in Britain’s roads and 300,000 in London.

The story had been sold to the Daily Mail in Manchester by Ron Kennedy of the Star News agency in Blackburn. Kennedy had noticed a Lancashire Evening Telegraph story about road excavations and in a telephone call to the Borough Engineer’s department had checked the annual number of holes in the road. Lennon had a problem with the words of the final verse, however, not being able to think of how to connect “Now they know how many holes it takes to” and “the Albert Hall”. His friend Terry Doran suggested that the holes would “fill” the Albert Hall.

The story had been sold to the Daily Mail in Manchester by Ron Kennedy of the Star News agency in Blackburn. Kennedy had noticed a Lancashire Evening Telegraph story about road excavations and in a telephone call to the Borough Engineer’s department had checked the annual number of holes in the road. Lennon had a problem with the words of the final verse, however, not being able to think of how to connect “Now they know how many holes it takes to” and “the Albert Hall”. His friend Terry Doran suggested that the holes would “fill” the Albert Hall.

Drug culture

McCartney said about the line “I’d love to turn you on”, which concludes both verse sections: “This was the time of Tim Leary’s ‘Turn on, tune in, drop out’ and we wrote, ‘I’d love to turn you on.’ John and I gave each other a knowing look: ‘Uh-huh, it’s a drug song. You know that, don’t you?’ “George Martin commented that he had always suspected that the line “found my way upstairs and had a smoke” was a drug reference, recalling how the Beatles would “disappear and have a little puff”, presumably of marijuana, but not in front of him. “When [Martin] was doing his TV programme on Pepper”, McCartney recalled later, “he asked me, ‘Do you know what caused Pepper?’ I said, ‘In one word, George, drugs. Pot.’ And George said, ‘No, no. But you weren’t on it all the time.’ ‘Yes, we were.’ Sgt. Pepper was a drug album.”

Other reference points

Author Neil Sinyard attributed the third-verse line “The Englisfh Army had just won the war” to Lennon’s role in the film How I Won the War, which he had filmed during September and October 1966. Sinyard said: “It’s hard to think of [the verse] … without automatically associating it with Richard Lester’s film.”

The middle-eight that McCartney provided for “A Day in the Life” was a short piano piece he had been working on independently, with lyrics about a commuter whose uneventful morning routine leads him to drift off into a dream.] McCartney had written the piece as a wistful recollection of his younger years, which included riding the 82 bus to school, smoking, and going to class. This theme—the Beatles’ youth in the north of England—matched that of “Penny Lane” (a street in Liverpool) and “Strawberry Fields Forever” (an orphanage behind Lennon’s house), two songs written for the album but were released instead as a double A-side single

Musical structure and development

Basic track

The Beatles began recording the song, with a working title of “In the Life of …” at EMI’s Studio Two on 19 January 1967. The line-up as they rehearsed the track was Lennon on piano, McCartney on Hammond organ, George Harrison on acoustic guitar, and Ringo Starr on congas. The band then taped four takes of the rhythm track, by which point Lennon had switched to acoustic guitar and McCartney to piano, with Harrison now playing maracas.

As a link between the end of the second verse, where Lennon sings “I’d love to turn you on”, and the start of McCartney’s middle-eight, the band included a 24-bar bridge. At first, the Beatles were not sure how to fill this link section. At the conclusion of the session on 19 January, the transition consisted of a simple repeated piano chord and the voice of assistant Mal Evans counting out the bars. Evans’ voice was treated with gradually increasing amounts of echo. The 24-bar bridge ended with the sound of an alarm clock triggered by Evans. Although the original intent was to edit out the ringing alarm clock when the section was filled in, it complemented McCartney’s piece – which begins with the line “Woke up, fell out of bed” – so the decision was made to keep the sound.

The track was refined with remixing and additional parts added on 20 January and 3 February. During the latter session, McCartney and Starr re-recorded their contributions on bass guitar and drums, respectively. Starr later highlighted his fills on the song as typical of an approach whereby “I try to become an instrument; play the mood of the song. For example, ‘Four thousand holes in Blackburn, Lancashire,’ – boom ba bom. I try to show that; the disenchanting mood.” As on the 1966 track “Rain”, music journalist Ben Edmonds recognizes Starr’s playing as reflective of his empathy with Lennon’s songwriting. In Edmonds’ description, the drumming on “A Day in the Life” “transcends timekeeping to embody psychedelic drift – mysterious, surprising, without losing sight of its rhythmic role”.

Orchestra

The orchestral portions of “A Day in the Life” reflect Lennon and McCartney’s interest in the work of avant-garde composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio and John Cage. To fill the empty 24-bar middle section, Lennon’s request to George Martin, the band’s producer, was that the orchestra should provide “a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world”. McCartney suggested having the musicians improvise over the segment. To allay concerns that classically trained musicians would be unable to do this, Martin wrote a loose score for the section. Using the rhythm implied by Lennon’s staggered intonation on the words “turn you on”, the score was an extended, atonal crescendo that encouraged the musicians to improvise within the defined framework. The orchestral part was recorded on 10 February 1967 in Studio One at EMI Studios, with Martin and McCartney conducting a 40-piece orchestra. The recording session was completed at a total cost of £367 (equivalent to £6,007 in 2015) for the players, an extravagance at the time. Martin later described explaining his score to the puzzled orchestra:

The orchestral portions of “A Day in the Life” reflect Lennon and McCartney’s interest in the work of avant-garde composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio and John Cage. To fill the empty 24-bar middle section, Lennon’s request to George Martin, the band’s producer, was that the orchestra should provide “a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world”. McCartney suggested having the musicians improvise over the segment. To allay concerns that classically trained musicians would be unable to do this, Martin wrote a loose score for the section. Using the rhythm implied by Lennon’s staggered intonation on the words “turn you on”, the score was an extended, atonal crescendo that encouraged the musicians to improvise within the defined framework. The orchestral part was recorded on 10 February 1967 in Studio One at EMI Studios, with Martin and McCartney conducting a 40-piece orchestra. The recording session was completed at a total cost of £367 (equivalent to £6,007 in 2015) for the players, an extravagance at the time. Martin later described explaining his score to the puzzled orchestra:

What I did there was to write … the lowest possible note for each of the instruments in the orchestra. At the end of the twenty-four bars, I wrote the highest note … near a chord of E major. Then I put a squiggly line right through the twenty-four bars, with reference points to tell them roughly what note they should have reached during each bar … Of course, they all looked at me as though I were completely mad.

McCartney had originally wanted a 90-piece orchestra, but this proved impossible. Instead, the semi-improvised segment was recorded multiple times, filling a separate four-track tape machine, and the four different recordings were overdubbed into a single massive crescendo. The results were successful; in the final edit of the song, the orchestral bridge is reprised after the final verse.

The Beatles hosted the orchestral session as a 1960s-style happening, with guests including Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Donovan, Pattie Boyd, Michael Nesmith, and members of the psychedelic design collective The Fool. Overseen by Tony Bramwell of NEMS Enterprises, the event was filmed for use in a projected television special that never materialised. Reflecting the Beatles’ taste for experimentation and the avant garde, the orchestra players were asked to wear formal dress and then given a costume piece as a contrast with this attire. This resulted in different players wearing anything from fake noses to fake stick-on nipples. Martin recalled that the lead violinist performed wearing a gorilla paw, while a bassoon player placed a balloon on the end of his instrument.

At the end of the night, the four Beatles and some of their guests overdubbed an extended humming sound to close the song – an idea that they later discarded. According to Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn, the tapes from this 10 February orchestral session reveal the guests breaking into loud applause following the second orchestral passage. Among the EMI staff attending the event, one recalled how Ron Richards, the Hollies’ producer, was stunned by the music he had heard; in Lewisohn’s description, Richards ” with his head in his hands, saying ‘I just can’t believe it … I give up.'” Martin later offered his own opinion of the orchestral session: “part of me said ‘We’re being a bit self-indulgent here.’ The other part of me said ‘It’s bloody marvellous!'”

Final chord

Following the final orchestral crescendo, the song ends with one of the most famous final chords in music history. Overdubbed in place of the vocal experiment from 10 February, this chord was added during a session at EMI’s Studio Two on 22 February. Lennon, McCartney, Starr and Evans shared three different pianos, with Martin on a harmonium, and all played an E-major chord simultaneously. The chord was made to ring out for over forty seconds by increasing the recording sound level as the vibration faded out. Towards the end of the chord the recording level was so high that listeners can hear the sounds of the studio, including rustling papers and a squeaking chair.

Following the final orchestral crescendo, the song ends with one of the most famous final chords in music history. Overdubbed in place of the vocal experiment from 10 February, this chord was added during a session at EMI’s Studio Two on 22 February. Lennon, McCartney, Starr and Evans shared three different pianos, with Martin on a harmonium, and all played an E-major chord simultaneously. The chord was made to ring out for over forty seconds by increasing the recording sound level as the vibration faded out. Towards the end of the chord the recording level was so high that listeners can hear the sounds of the studio, including rustling papers and a squeaking chair.

This final E chord represents a VI to the song’s tonic G major. However, Dominic Pedler argues that the preceding chord changes (from F (“them all”) to E (“Now they know”) Em7 (“takes to fill”) C (“love to turn you”) and B (“on”)) followed by the chromatic ascent, shift one’s sense of the tonic from G to E, creating a different feeling from the usual emotional uplift associated with a VI modulation.

Also present at the session was David Crosby of the Byrds. He recalled his reaction to hearing the completed song: “man, I was a dish-rag. I was floored. It took me several minutes to be able to talk after that.” Due to the multiple takes required to perfect the orchestral cacophony and the final chord, the total duration of time spent recording “A Day in the Life” was 34 hours. In contrast, the Beatles’ debut album, Please Please Me, had been recorded in its entirety in only 10 hours, 45 minutes.

I Want To Hold Your Hand

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles. Written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, and recorded in October 1963, it was the first Beatles record to be made using four-track equipment.

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles. Written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, and recorded in October 1963, it was the first Beatles record to be made using four-track equipment.

With advance orders exceeding one million copies in the United Kingdom, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” would have gone straight to the top of the British record charts on its day of release (29 November 1963) had it not been blocked by the group’s first million seller “She Loves You”, their previous UK single, which was having a resurgence of popularity following intense media coverage of the group. Taking two weeks to dislodge its predecessor, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” stayed at number one for five weeks and remained in the UK top 50 for 21 weeks in total.

It was also the group’s first American number one, entering the Billboard Hot 100 chart on 18 January 1964 at number 45 and starting the British invasion of the American music industry. By 1 February it held the number-one spot, and stayed there for seven weeks before being replaced by “She Loves You”, a reverse scenario of what had occurred in Britain. It remained on the Billboard chart for 15 weeks. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” became the Beatles’ best-selling single worldwide. In 2013, Billboard magazine named it the 44th biggest hit of “all-time” on the Billboard Hot 100 charts.

Strawberry Fields Forever

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles. The song was written by John Lennon and credited to the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership. It was inspired by Lennon’s memories of playing in the garden of Strawberry Field, a Salvation Army children’s home near where he grew up in Liverpool.\

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles. The song was written by John Lennon and credited to the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership. It was inspired by Lennon’s memories of playing in the garden of Strawberry Field, a Salvation Army children’s home near where he grew up in Liverpool.\

The song was the first track recorded during the sessions for the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), and was intended for inclusion on the album. Instead, with the group under record-company pressure to release a single, it was issued in February 1967 as a double A-side with “Penny Lane”. The combination reached number two in the UK Singles Chart, breaking the band’s four-year run of chart-topping singles in the UK, while “Strawberry Fields Forever” peaked at number eight on the Billboard Hot 100 in the US.

Lennon considered the song his greatest accomplishment. The track incorporates reverse-recorded instrumentation and tape loops, and was created from the editing together of two separate versions of the song – each one entirely different in tempo, mood and musical key. The song was later included on the US Magical Mystery Tour LP (although not on the British double EP package of the same name).

“Strawberry Fields Forever” is one of the defining works of the psychedelic rock genre and has been covered by many artists. The Beatles made a promotional film clip for the song that is similarly recognized for its influence in the medium of music video. The Strawberry Fields memorial in New York’s Central Park is named after the song.

Strawberry Field was the name of a Salvation Army children’s home just around the corner from Lennon’s childhood home in Woolton, a suburb of Liverpool. Lennon and his childhood friends Pete Shotton, Nigel Walley, and Ivan Vaughan used to play in the wooded garden behind the home. One of Lennon’s childhood treats was the garden party held each summer in Calderstones Park, near the home, where a Salvation Army band played. Lennon’s aunt Mimi Smith recalled: “As soon as we could hear the Salvation Army band starting, John would jump up and down shouting, ‘Mimi, come on. We’re going to be late.'”

Lennon’s “Strawberry Fields Forever” and McCartney’s “Penny Lane” shared the theme of nostalgia for their early years in Liverpool. Although both referred to actual locations, the two songs also had strong surrealistic and psychedelic overtones. Producer George Martin said that when he first heard “Strawberry Fields Forever”, he thought it conjured up a “hazy, impressionistic dreamworld”.

The Beatles had just retired from touring after one of the most difficult periods of their career, including the “more popular than Jesus” controversy and the band’s unintentional snubbing of Philippines First Lady Imelda Marcos. Lennon talked about the song in 1980: “I was different all my life. The second verse goes, ‘No one I think is in my tree.’ Well, I was too shy and self-doubting. Nobody seems to be as hip as me is what I was saying. Therefore, I must be crazy or a genius – ‘I mean it must be high or low’ “, and explaining that the song was “psycho-analysis set to music”.

Lennon began writing the song in Almería, Spain, during the filming of Richard Lester’s How I Won the War in September–October 1966. The earliest demo of the song, recorded in Almería, had no refrain and only one verse: “There’s no one on my wavelength / I mean, it’s either too high or too low / That is you can’t you know tune in but it’s all right / I mean it’s not too bad”. He revised the words to this verse to make them more obscure, then wrote the melody and part of the lyrics to the refrain (which then functioned as a bridge and did not yet include a reference to Strawberry Fields). He then added another verse and the mention of Strawberry Fields. The first verse on the released version was the last to be written, close to the time of the song’s recording. For the refrain, Lennon was again inspired by his childhood memories: the words “nothing to get hung about” were inspired by Aunt Mimi’s strict order not to play in the grounds of Strawberry Field, to which Lennon replied, “They can’t hang you for it.” The first verse Lennon wrote became the second in the released version, and the second verse Lennon wrote became the last in the release.

The song was originally written on acoustic guitar in the key of C major. The recorded version is approximately in B♭ major; owing to manipulation of the recording speed, the finished version is not in standard pitch (some, for instance, consider that the tonic is A).

The introduction was played by McCartney on a Mellotron, and involves a I–ii–I–♭VII–IV progression. The vocals enter with the chorus instead of a verse. In fact we are not “taken down” to the tonic key, but to “non-diatonic chords and secondary dominants” combining with “chromatic melodic tension intensified through outrageous harmonisation and root movement”. The phrase “to Strawberry” for example begins with a somewhat dissonant G melody note against a prevailing F minor key, then uses the semi-tone dissonance B♭ and B notes (the natural and sharpened 11th degrees against the Fm chord) until the consonant F note is reached on “Fields”. The same series of mostly dissonant melody notes cover the phrase “nothing is real” against the prevailing F♯7 chord (in A key).

A half-measure complicates the meter of the verses, as well as the fact that the vocals begin in the middle of the first measure. The first verse comes after the refrain, and is eight measures long. The verse (for example “Always, no sometimes …”) starts with an F major chord in the key of B♭ (or E chord in the key of A) (V), which progresses to G minor, the submediant, a deceptive cadence. According to Alan Pollack, the “approach-avoidance tactic” (i.e., the deceptive cadence) is encountered in the verse, as the leading-tone, A, appearing on the words “Always know”, “I know when”, “I think I know of thee” and “I think I disagree”, never resolves into a I chord (A in A key) directly as expected. Instead, at the end of the verse, the leading note, harmonized as part of the dominant chord, resolves to the prevailing tonic (B♭) at the end of the verse, after tonicizing the subdominant (IV) E♭ chord, on “disagree”.

In the middle of the second chorus, the “funereal brass” is introduced, stressing the ominous lyrics. After three verses and four choruses, the line “Strawberry Fields Forever” is repeated three times, and the song fades out with guitar, cello and swarmandal instrumentation. The song fades back in after a few seconds into the “nightmarish” ending, with the Mellotron playing in a haunting tone – one achieved by recording the Mellotron “Swinging Flutes” setting in reverse – scattered drumming, and Lennon murmuring, after which the song completes.

The working title was “It’s Not Too Bad”, and Geoff Emerick, the sound engineer, remembered it being “just a great, great song, that was apparent from the first time John sang it for all of us, playing an acoustic guitar.” Recording began on 24 November 1966, in Abbey Road’s Studio Two on a 4-track machine. It took 45 hours to record, spread over five weeks. The song was meant to be on the band’s 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, but was released as a single instead.

The band recorded three distinct versions of the song. After Lennon played the song for the other Beatles on his acoustic guitar, the band recorded the first take. Lennon played an Epiphone Casino; McCartney played a Mellotron, a tape replay keyboard instrument purchased by Lennon on 12 August 1965 (with another model hired in after encouragement from keyboardist Mike Pinder of the Moody Blues); George Harrison played electric slide guitar, and Ringo Starr played drums. The first recorded take began with the verse “Living is easy …”, instead of the chorus, “Let me take you down”, which starts the released version. The first verse also led directly to the second, with no chorus between. Lennon’s vocals were automatically double-tracked from the words “Strawberry Fields Forever” through the end of the last verse. The last verse, beginning “Always, no sometimes”, has three-part harmonies, with McCartney and Harrison singing “dreamy background vocals”. This version was soon abandoned and went unreleased until the Anthology 2 compilation in 1996.

The band recorded three distinct versions of the song. After Lennon played the song for the other Beatles on his acoustic guitar, the band recorded the first take. Lennon played an Epiphone Casino; McCartney played a Mellotron, a tape replay keyboard instrument purchased by Lennon on 12 August 1965 (with another model hired in after encouragement from keyboardist Mike Pinder of the Moody Blues); George Harrison played electric slide guitar, and Ringo Starr played drums. The first recorded take began with the verse “Living is easy …”, instead of the chorus, “Let me take you down”, which starts the released version. The first verse also led directly to the second, with no chorus between. Lennon’s vocals were automatically double-tracked from the words “Strawberry Fields Forever” through the end of the last verse. The last verse, beginning “Always, no sometimes”, has three-part harmonies, with McCartney and Harrison singing “dreamy background vocals”. This version was soon abandoned and went unreleased until the Anthology 2 compilation in 1996.

Four days later the band reassembled to try a different arrangement. The second version of the song featured McCartney’s Mellotron introduction followed by the refrain. They recorded five takes of the basic tracks for this arrangement (two of which were false starts) with the last being chosen as best and subjected to further overdubs. Lennon’s final vocal was recorded with the tape running fast so that when played back at normal speed the tonality would be altered, giving his voice a slurred sound. This version was used for the first minute of the released recording.

After recording the second version of the song, Lennon wanted to do something different with it, as Martin remembered: “He’d wanted it as a gentle dreaming song, but he said it had come out too raucous. He asked me if I could write him a new line-up with the strings. So I wrote a new score (with four trumpets and three cellos) and we recorded that, but he didn’t like it.” Meanwhile, on 8 and 9 December, another basic track was recorded, using a Mellotron, electric guitar, piano, backwards-recorded cymbals, and the swarmandel (or swordmandel), an Indian version of the zither.

After reviewing the tapes of Martin’s version and the original, Lennon told Martin that he liked both versions, although Martin had to tell Lennon that the orchestral score was at a faster tempo and in a higher key (B major) than the first version (A major). Lennon said, “You can fix it, George”, giving Martin and Emerick the difficult task of joining the two takes together. With only a pair of editing scissors, two tape machines and a vari-speed control, Emerick compensated for the differences in key and speed by increasing the speed of the first version and decreasing the speed of the second. He then spliced the versions together, starting the orchestral score in the middle of the second chorus. (Since the first version did not include a chorus after the first verse, he also spliced in the first seven words of the chorus from elsewhere in the first version.) The pitch-shifting in joining the versions gave Lennon’s lead vocal a slightly other-worldly “swimming” quality.

After reviewing the tapes of Martin’s version and the original, Lennon told Martin that he liked both versions, although Martin had to tell Lennon that the orchestral score was at a faster tempo and in a higher key (B major) than the first version (A major). Lennon said, “You can fix it, George”, giving Martin and Emerick the difficult task of joining the two takes together. With only a pair of editing scissors, two tape machines and a vari-speed control, Emerick compensated for the differences in key and speed by increasing the speed of the first version and decreasing the speed of the second. He then spliced the versions together, starting the orchestral score in the middle of the second chorus. (Since the first version did not include a chorus after the first verse, he also spliced in the first seven words of the chorus from elsewhere in the first version.) The pitch-shifting in joining the versions gave Lennon’s lead vocal a slightly other-worldly “swimming” quality.

Yesterday

is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, written by Paul McCartney (credited to Lennon–McCartney), and first released on the album Help! in the United Kingdom in August 1965.

is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, written by Paul McCartney (credited to Lennon–McCartney), and first released on the album Help! in the United Kingdom in August 1965.

“Yesterday”, with the B-side “Act Naturally”, was released as a single in the United States in September 1965.. The song also appeared on the UK EP “Yesterday” in March 1966 and the Beatles’ US album Yesterday and Today, released in June 1966.

McCartney’s vocal and acoustic guitar, together with a string quartet, essentially made for the first solo performance of the band

Ostensibly simple, featuring only McCartney playing an Epiphone Texan steel-string acoustic guitar backed by a string quartet in one of the Beatles’ first uses of session musicians, “Yesterday” has two contrasting sections, differing in melody and rhythm, producing a sense of disjunction.

The first section (“Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away …”) opens with an F chord (the 3rd of the chord is omitted), then moving to Em7 before proceeding to A7 and then to D-minor. In this sense, the opening chord is a decoy; as musicologist Alan Pollack points out, the home key (F-major) has little time to establish itself before “heading towards the relative D-minor.” He points out that this diversion is a compositional device commonly used by Lennon and McCartney, which he describes as “delayed gratification”.

The second section (“Why she had to go I don’t know …”) is, according to Pollack, less musically surprising on paper than it sounds. Starting with Em7, the harmonic progression quickly moves through the A-major, D-minor, and (closer to F-major) B♭, before resolving back to F-major, and at the end of this, McCartney holds F while the strings descend to resolve to the home key to introduce the restatement of the first section, before a brief hummed closing phrase.

Pollack described the scoring as “truly inspired”, citing it as an example of “[Lennon & McCartney’s] flair for creating stylistic hybrids”; in particular, he praises the “ironic tension drawn between the schmaltzy content of what is played by the quartet and the restrained, spare nature of the medium in which it is played.”

The tonic key of the song is F major (although, since McCartney tuned his guitar down a whole step, he was playing the chords as if it were in G), where the song begins before veering off into the key of D minor. It is this frequent use of the minor, and the ii-V7 chord progression (Em and A7 chords in this case) leading into it, that gives the song its melancholy aura. The A7 chord is an example of a secondary dominant, specifically a V/vi chord. The G7 chord in the bridge is another secondary dominant, in this case a V/V chord, but rather than resolve it to the expected chord, as with the A7 to Dm in the verse, McCartney instead follows it with the IV chord, a B♭. This motion creates a descending chromatic line of C–B–B♭–A to accompany the title lyric.

The string arrangement reinforces the song’s air of sadness, in the groaning cello line that connects the two halves of the bridge, notably the “blue” seventh in the second bridge pass (the E♭ played after the vocal line, “I don’t know / she wouldn’t say”) and in the descending run by the viola that segues the bridge back into the verses, mimicked by McCartney’s vocal on the second pass of the bridge. This viola line, the “blue” cello phrase, the high A sustained by the violin over the final verse and the minimal use of vibrato are elements of the string arrangement attributable to McCartney rather than George Martin.

When the song was performed on The Ed Sullivan Show, it was done in the above-mentioned key of F, with McCartney as the only Beatle to perform, and the studio orchestra providing the string accompaniment. However, all of the Beatles played in a G-major version when the song was included in tours in 1965 and 1966.

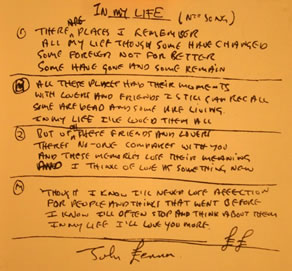

In My Life

In my life is a song by the Beatles released on the 1965 album Rubber Soul, written mainly by John Lennon and credited to Lennon–McCartney.

In my life is a song by the Beatles released on the 1965 album Rubber Soul, written mainly by John Lennon and credited to Lennon–McCartney.

The song originated with Lennon, and while Paul McCartney contributed to the final version, he and Lennon later disagreed over the extent of his contributions (specifically the melody).

George Martin contributed the instrumental bridge. It is ranked 23rd on Rolling Stone’s “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time” as well as fifth on their list of the Beatles’ 100 Greatest Songs.

The song placed second on CBC’s 50 Tracks. Mojo magazine named it the best song of all time in 2000

Recording

The song was recorded on 18 October 1965, and was complete except for the instrumental bridge. At that time, Lennon had not decided what instrument to use, but he subsequently asked George Martin to play a piano solo, suggesting “something Baroque-sounding”. Martin wrote a Bach-influenced piece that he found he could not play at the song’s tempo. On 22 October, the solo was recorded with the tape running at half speed, so when played back at normal pace the piano was twice as fast and an octave higher, solving the performance challenge and also giving the solo a unique timbre, reminiscent of a harpsichord

The song was recorded on 18 October 1965, and was complete except for the instrumental bridge. At that time, Lennon had not decided what instrument to use, but he subsequently asked George Martin to play a piano solo, suggesting “something Baroque-sounding”. Martin wrote a Bach-influenced piece that he found he could not play at the song’s tempo. On 22 October, the solo was recorded with the tape running at half speed, so when played back at normal pace the piano was twice as fast and an octave higher, solving the performance challenge and also giving the solo a unique timbre, reminiscent of a harpsichord

Something

Something is a song by the Beatles, written by George Harrison and released on the band’s 1969 album Abbey Road. It was also issued as a single coupled with another track from the album, “Come Together”. “Something” was the first Harrison composition to appear as a Beatles A-side, and the only song written by him to top the US charts before the band’s break-up in April 1970. The single was also one of the first Beatles singles to contain tracks already available on an LP album.

Something is a song by the Beatles, written by George Harrison and released on the band’s 1969 album Abbey Road. It was also issued as a single coupled with another track from the album, “Come Together”. “Something” was the first Harrison composition to appear as a Beatles A-side, and the only song written by him to top the US charts before the band’s break-up in April 1970. The single was also one of the first Beatles singles to contain tracks already available on an LP album.

The song drew high praise from the band’s primary songwriters, John Lennon and Paul McCartney; Lennon stated that “Something” was the best song on Abbey Road, while McCartney considered it the best song Harrison had written. As well as critical acclaim, the single achieved commercial success, topping the Billboard Hot 100 in the United States and making the top five in the United Kingdom. The song has been covered by over 150 artists, making it the second-most covered Beatles song after “Yesterday”. Artists who have covered the song include Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, James Brown, Shirley Bassey, Tony Bennett, Andy Williams, Smokey Robinson, Ike & Tina Turner, Eric Clapton, Joe Cocker, Isaac Hayes, Julio Iglesias and Neil Diamond. Harrison said his favorite version of the song was James Brown’s, which he kept in his personal jukebox.

Background and inspiration

George Harrison began writing “Something” in September 1968, during a session for the Beatles’ self-titled double album, commonly known as “the White Album”. In his autobiography, I, Me Mine, he recalls working on the melody on a piano, while Paul McCartney carried out overdubs in a neighboring studio at London’s Abbey Road Studios. Harrison put the composition “on ice” at first, believing that with the tune having come to him so easily, it might have been the melody from another song. In I, Me, Mine, he adds that the middle eight for “Something” “took some time to sort out”.

The song’s opening lyric was taken from the title of “Something in the Way She Moves”, a track by Harrison’s fellow Apple Records artist James Taylor. While musically Harrison imagined the composition in the style of Ray Charles, his inspiration for “Something” was his wife, Pattie Boyd. In her 2007 autobiography, Wonderful Today, Boyd recalls: “He told me, in a matter-of-fact way, that he had written it for me. I thought it was beautiful …” Boyd discusses the song’s subsequent popularity among other recording artists and concludes: “My favourite [version] was the one by George Harrison, which he played to me in the kitchen at Kinfauns.”

Having begun to write love songs that were directed at both God and a woman, with his White Album track “Long, Long, Long”, Harrison later cited alternative sources for his inspiration for “Something”. In early 1969, according to author Joshua Greene, Harrison told his friends from the Hare Krishna Movement that the song was about the Hindu deity Krishna; in an interview with Rolling Stone magazine in 1976, he said of his approach to writing love songs: “all love is part of a universal love. When you love a woman, it’s the God in her that you see.” By 1996, Harrison had denied writing “Something” for Boyd, adding that “everybody presumed I wrote it about Pattie” because of the promotional film accompanying the release of the Beatles’ recording, which showed each member of the band with his respective wife.

Composition

In the version issued on the Beatles’ 1969 album Abbey Road, which was the first release for the song, “Something” runs at a speed of around 66 beats per minute and is in common time throughout. It begins with a five-note guitar figure, which functions as the song’s chorus, since it is repeated before each of the verses and also closes the track. The melody is in the key of C major until the eight-measure-long bridge, or middle eight, which is in the key of A major. Harrison biographer Simon Leng identifies “harmonic interest … [in] almost every line” of the song, as the melody follows a series of descending half-steps from the tonic over the verses, a structure that is then mirrored in the new key, through the middle eight. The melody returns to C major for the guitar solo, the third verse, and the outro.

While Leng considers that, lyrically and musically, “Something” reflects “doubt and striving to attain an uncertain goal”, author Ian Inglis writes of the confident statements that Harrison makes throughout regarding his feelings for Boyd. Referring to lines in the song’s verses, Inglis writes: “there is a clear and mutual confidence in the reciprocal nature of their love; he muses that [Boyd] ‘attracts me like no other lover’ and ‘all I have to do is think of her,’ but he is equally aware that she feels the same, that ‘somewhere in her smile, she knows.'” Similarly, when Harrison sings in the middle eight that “You’re asking me will my love grow / I don’t know, I don’t know”, Inglis interprets the words as “not an indication of uncertainty, but a wry reflection that his love is already so complete that it may simply be impossible for it to become any greater”. Richie Unterberger of AllMusic describes “Something” as “an unabashedly straightforward and sentimental love song” written at a time “when most of the Beatles’ songs were dealing with non-romantic topics or presenting cryptic and allusive lyrics even when they were writing about love”.

Hey Jude

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, written by Paul McCartney and credited to Lennon–McCartney. The ballad evolved from “Hey Jules”, a song McCartney wrote to comfort John Lennon’s son, Julian, during his parents’ divorce. “Hey Jude” begins with a verse-bridge structure incorporating McCartney’s vocal performance and piano accompaniment; further instrumentation is added as the song progresses. After the fourth verse, the song shifts to a fade-out coda that lasts for more than four minutes.

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, written by Paul McCartney and credited to Lennon–McCartney. The ballad evolved from “Hey Jules”, a song McCartney wrote to comfort John Lennon’s son, Julian, during his parents’ divorce. “Hey Jude” begins with a verse-bridge structure incorporating McCartney’s vocal performance and piano accompaniment; further instrumentation is added as the song progresses. After the fourth verse, the song shifts to a fade-out coda that lasts for more than four minutes.

“Hey Jude” was released in August 1968 as the first single from the Beatles’ record label Apple Records. More than seven minutes in length, it was at the time the longest single ever to top the British charts. It also spent nine weeks at number one in the United States, the longest for any Beatles single. “Hey Jude” tied the “all-time” record, at the time, for the longest run at the top of the US charts. The single has sold approximately eight million copies and is frequently included on professional critics’ lists of the greatest songs of all time. In 2013, Billboard named it the 10th biggest song of all time.

Let It Be

is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, released in March 1970 as a single, and (in an alternate mix) as the title track of their album Let It Be. At the time, it had the highest debut on the Billboard Hot 100, reaching number 6. It was written and sung by Paul McCartney. It was their final single before McCartney announced his departure from the band. Both the Let It Be album and the US single “The Long and Winding Road” were released after McCartney’s announced departure from and the subsequent break-up of the group.

is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, released in March 1970 as a single, and (in an alternate mix) as the title track of their album Let It Be. At the time, it had the highest debut on the Billboard Hot 100, reaching number 6. It was written and sung by Paul McCartney. It was their final single before McCartney announced his departure from the band. Both the Let It Be album and the US single “The Long and Winding Road” were released after McCartney’s announced departure from and the subsequent break-up of the group.

Origins

McCartney said he had the idea of “Let It Be” after he had a dream about his mother during the tense period surrounding the sessions for The Beatles (“the White Album”) in 1968. According to McCartney, the song’s reference to “Mother Mary” was not biblical. The phrase has at times been used as a reference to the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ. Nevertheless, McCartney explained that his mother – who died of cancer when he was fourteen – was the inspiration for the “Mother Mary” lyric. He later said: “It was great to visit with her again. I felt very blessed to have that dream. So that got me writing ‘Let It Be’.” He also said in a later interview about the dream that his mother had told him, “It will be all right, just let it be.” When asked if the song referred to the Virgin Mary, McCartney has typically answered the question by assuring his fans that they can interpret the song however they like.

Recordings

The first rehearsal of “Let It Be” took place at Twickenham Film Studios on 3 January 1969, where the group had, the previous day, begun what would become the Let It Be film. During this stage of the film they were only recording on the mono decks used for syncing to the film cameras, and were not making multi-track recordings for release. A single take was recorded, with just McCartney on piano and vocals. The first attempt with the other Beatles was made on 8 January. Work continued on the song throughout the month. Multi-track recordings commenced on 23 January at Apple Studios.

The master take was recorded on 31 January 1969, as part of the “Apple studio performance” for the project. McCartney played Blüthner piano, Lennon played six-string electric bass (replaced by McCartney’s own bass part on the final version at the behest of George Martin), George Harrison and Ringo Starr assumed their conventional roles, on guitar and drums respectively, and Billy Preston contributed on organ. This was one of two performances of “Let It Be” that day. The first version, designated takes 27-A, would serve as the basis for all officially released versions of the song. The other version, take 27-B, was performed as part of the “live studio performance”, along with “Two of Us” and “The Long and Winding Road”. This performance, in which Lennon and Harrison harmonised with McCartney’s lead vocal and Harrison contributed a subdued guitar solo, can be seen in the film Let It Be.

The film performance of “Let It Be” has never been officially released as an audio recording. The lyrics in the two versions differ a little in the last verse. The studio version has mother Mary comes to me … there will be an answer, whereas the film version has mother Mary comes to me … there will be no sorrow. In addition, McCartney’s vocal performance is noticeably different in both versions: in the film version, it sounds a rough in certain moments since he is not using anti-pop on his mic; there are also a couple of falsetto vocals performed by him (extending the vocal ‘e’ on the word ‘be’), for instance in the ‘let it be’ line that precedes the second chorus. Finally, the instrumental progression featured on the middle of the song after the second chorus (that descends from F to C), which is played twice on all released studio versions, is played (or at least is shown being played) only once in the film.

On 30 April 1969, Harrison overdubbed a new guitar solo on the best take from 31 January. He overdubbed another solo on 4 January 1970. The first overdub solo was used for the original single release, and the second overdub solo was used for the original album release. Some fans mistakenly believe that there were two versions of the basic track – based mostly on the different guitar solos, but also on other differences in overdubs and mixes.

Come Together

Is a song by the Beatles written primarily by John Lennon and credited to Lennon–McCartney. The song is the opening track on the album Abbey Road and was also released as a single coupled with “Something”. The song reached the top of the charts in the United States and peaked at No. 4 in the United Kingdom.

Is a song by the Beatles written primarily by John Lennon and credited to Lennon–McCartney. The song is the opening track on the album Abbey Road and was also released as a single coupled with “Something”. The song reached the top of the charts in the United States and peaked at No. 4 in the United Kingdom.

“Come Together” started as Lennon’s attempt to write a song for Timothy Leary’s camp aign for governor of California against Ronald Reagan, which promptly ended when Leary was sent to prison for possession of marijuana.

Recording

Lennon played rhythm guitar and sang the vocal, McCartney played bass, Harrison played lead guitar, and Starr played drums. It was produced by George Martin and recorded at the end of July 1969 at Abbey Road Studios. In the intro, Lennon says: “shoot me”, which is accompanied by his handclaps and McCartney’s heavy bass riff. The famous Beatles’ “walrus” from “I Am the Walrus” and “Glass Onion” returns in the line “he got walrus gumboot”, followed by “he got Ono sideboard”.

Bluesman Muddy Waters is also mentioned in the song.

Music critic Ian MacDonald reports that McCartney sang a backing vocal, but recording engineer Geoff Emerick said that Lennon did all the vocals himself, and when a frustrated McCartney asked Lennon, “What do you want me to do on this track, John?”, Lennon replied, “Don’t worry, I’ll do the overdubs on this.

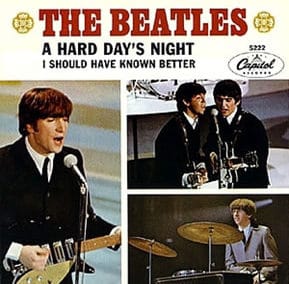

A Hard Day’s Night

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles. Written by John Lennon, and credited to Lennon–McCartney, it was released on the film soundtrack of the same name in 1964. It was also released in the UK as a single, with “Things We Said Today” as its B-side.

Is a song by the English rock band the Beatles. Written by John Lennon, and credited to Lennon–McCartney, it was released on the film soundtrack of the same name in 1964. It was also released in the UK as a single, with “Things We Said Today” as its B-side.

The song featured prominently on the soundtrack to the Beatles’ first feature film, A Hard Day’s Night, and was on their album of the same name. The song topped the charts in both the United Kingdom and United States when it was released as a single.

The American and British singles of “A Hard Day’s Night” as well as both the American and British albums of the same title all held the top position in their respective charts for a couple of weeks in August 1964, the first time any artist had accomplished this feat.

Title

The song’s title originated from something said by Ringo Starr, the Beatles’ drummer. Starr described it this way in an interview with disc jockey Dave Hull in 1964: “We went to do a job, and we’d worked all day and we happened to work all night. I came up still thinking it was day I suppose, and I said, ‘It’s been a hard day …’ and I looked around and saw it was dark so I said, ‘… night!’ So we came to ‘A Hard Day’s Night.'”

Starr’s statement was the inspiration for the title of the film, which in turn inspired the composition of the song. According to Lennon in a 1980 interview with Playboy magazine: “I was going home in the car and Dick Lester [director of the movie] suggested the title, ‘Hard Day’s Night’ from something Ringo had said. I had used it in In His Own Write [a book Lennon was writing then], but it was an off-the-cuff remark by Ringo. You know, one of those malapropisms. A Ringo-ism, where he said it not to be funny … just said it. So Dick Lester said, ‘We are going to use that title.'”

In a 1994 interview for The Beatles Anthology, however, McCartney disagreed with Lennon’s recollections, basically stating that it was the Beatles, and not Lester, who had come up with the idea of using Starr’s verbal misstep: “The title was Ringo’s. We’d almost finished making the film, and this fun bit arrived that we’d not known about before, which was naming the film. So we were sitting around at Twickenham studios having a little brain-storming session … and we said, ‘Well, there was something Ringo said the other day.’ Ringo would do these little malapropisms, he would say things slightly wrong, like people do, but his were always wonderful, very lyrical … they were sort of magic even though he was just getting it wrong. And he said after a concert, ‘Phew, it’s been a hard day’s night

Revolution

Is a song by the Beatles, written by John Lennon and credited to Lennon–McCartney. Three versions of the song were recorded in 1968: a slow, bluesy arrangement (titled “Revolution 1”) for the Beatles’ self-titled double album, commonly known as “the White Album”; a more abstract musical collage (titled “Revolution 9”) that originated as the latter part of “Revolution 1” and appears on the same album; and a faster, hard rock version similar to “Revolution 1”, released as the B-side of the “Hey Jude” single.

Is a song by the Beatles, written by John Lennon and credited to Lennon–McCartney. Three versions of the song were recorded in 1968: a slow, bluesy arrangement (titled “Revolution 1”) for the Beatles’ self-titled double album, commonly known as “the White Album”; a more abstract musical collage (titled “Revolution 9”) that originated as the latter part of “Revolution 1” and appears on the same album; and a faster, hard rock version similar to “Revolution 1”, released as the B-side of the “Hey Jude” single.

Although the single version was issued first, it was recorded several weeks after “Revolution 1”, as a re-make specifically intended for release as a single.

Inspired by political protests in early 1968, Lennon’s lyrics expressed doubt in regard to some of the tactics. When the single version was released in August, the political left viewed it as betraying their cause. The release of the album version in November indicated Lennon’s uncertainty about destructive change, with the phrase “count me out” recorded differently as “count me out, in”. In 1987, the song became the first Beatles recording to be licensed for a television commercial, which prompted a lawsuit from the surviving members of the group.

She Loves You

Is a song written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney and recorded by English rock group the Beatles for release as a single in 1963. The single set and surpassed several records in the United Kingdom charts, and set a record in the United States as one of the five Beatles songs that held the top five positions in the American charts simultaneously on 4 April 1964. It is their best-selling single and the best selling single of the 1960s in the United Kingdom.

Is a song written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney and recorded by English rock group the Beatles for release as a single in 1963. The single set and surpassed several records in the United Kingdom charts, and set a record in the United States as one of the five Beatles songs that held the top five positions in the American charts simultaneously on 4 April 1964. It is their best-selling single and the best selling single of the 1960s in the United Kingdom.

In November 2004, Rolling Stone ranked “She Loves You” number 64 on their list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. In August 2009, at the end of its “Beatles Weekend”, BBC Radio 2 announced that “She Loves You” was the Beatles’ all-time best-selling single in the UK based on information compiled by The Official Charts Company.

Lennon and McCartney started composing “She Loves You” on 26 June 1963 after a concert at the Majestic Ballroom in Newcastle upon Tyne during their tour with Roy Orbison and Gerry and the Pacemakers. They began writing the song on the tour bus, and continued later that night at their hotel in Newcastle.

In 2000, McCartney said the initial idea for the song began with Bobby Rydell’s hit “Forget Him” with its call and response pattern, and that “as often happens, you think of one song when you write another … I’d planned an ‘answering song’ where a couple of us would sing ‘she loves you’ and the other ones would answer ‘yeah yeah’. We decided that was a crummy idea but at least we then had the idea of a song called ‘She Loves You’. So we sat in the hotel bedroom for a few hours and wrote it—John and I, sitting on twin beds with guitars.” It was completed the following day at McCartney’s family home in Forthlin Road, Liverpool.

Like many early Beatles songs, the title of “She Loves You” was framed around the use of personal pronouns. But unusually for a love song, the lyrics are not about the narrator’s love for someone else; instead the narrator functions as a helpful go-between for estranged lovers:

You think you lost your love,

Well, I saw her yesterday.

It’s you she’s thinking of –

And she told me what to say.

She says she loves you…

This idea was attributed by Lennon to McCartney in 1980: “It was Paul’s idea: instead of singing ‘I love you’ again, we’d have a third party. That kind of little detail is still in his work. He will write a story about someone. I’m more inclined to write about myself.”

Lennon, being mindful of Elvis Presley’s “All Shook Up”, wanted something equally as stirring: “I don’t know where the ‘yeah yeah yeah’ came from [but] I remember when Elvis did ‘All Shook Up’ it was the first time in my life that I had heard ‘uh huh’, ‘oh yeah’, and ‘yeah yeah’ all sung in the same song”. The song also included a number of falsetto “wooooo”‘s, which Lennon acknowledged as being inspired by the Isley Brothers’ recording of “Twist and Shout”, which the Beatles had earlier recorded, and which had also been inserted into the group’s previous single, “From Me to You”.

As Lennon later said: “We stuck it in everything”. McCartney recalls them playing the finished song on acoustic guitars to his father Jim at home immediately after the song was completed: “We went into the living room and said ‘Dad, listen to this. What do you think? And he said ‘That’s very nice son, but there’s enough of these Americanisms around. Couldn’t you sing ‘She loves you, yes, yes, yes!’. At which point we collapsed in a heap and said ‘No, Dad, you don’t quite get it!'” EMI recording engineer Norman Smith had a somewhat similar reaction, later recounting, “I was setting up the microphone when I first saw the lyrics on the music stand, ‘She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah, She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah, She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah, Yeah!’ I thought, Oh my God, what a lyric! This is going to be one that I do not like. But when they started to sing it—bang, wow, terrific, I was up at the mixer jogging around.”

The “yeah, yeah, yeah” refrain proved an immediate, effective, infectious musical hook. Unusually, the song starts with the hook right away, instead of introducing it after a verse or two. “She Loves You” does not include a bridge, instead using the refrain to join the various verses. The chords tend to change every two measures, and the harmonic scheme is mostly static.

The arrangement starts with a two-count of Ringo Starr’s drums, and his fills are an important part of the record throughout. The electric instruments are mixed higher than before, especially McCartney’s bass, adding to the sense of musical power that the record provides. The lead vocal is sung by Lennon and McCartney, switching between unison and harmony.

George Martin, the Beatles’ producer, questioned the validity of the major sixth chord that ends the song, an idea suggested by George Harrison. “They sort of finished on this curious singing chord which was a major sixth, with George [Harrison] doing the sixth and the others doing the third and fifth in the chord. It was just like a Glenn Miller arrangement.” The device had also been used by country music-influenced artists in the 1950s.

McCartney later reflected: “We took it to George Martin and sang ‘She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeeeeeaah …’ and that tight little sixth cluster we had at the end. George [Martin] said: ‘It’s very corny, I would never end on a sixth’. But we said ‘It’s such a great sound, it doesn’t matter'”. The Beatles: Complete Scores shows only the notes D (the fifth) and E (the sixth) sung for the final chord, while on the recording McCartney sang G (the root) as Harrison sang E and Lennon sang D.