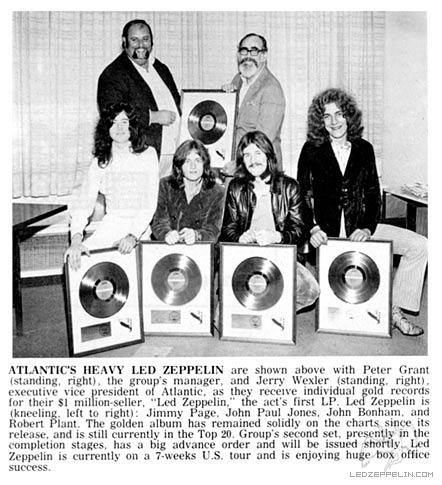

Atlantic Records is an American major record label founded in October 1947 by Ahmet Ertegün and Herb Abramson. Over its first 20 years of operation, Atlantic Records earned a reputation as one of the most important American recording labels, specializing in jazz, R&B and soul recordings by African-American musicians including Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave, Ruth Brown and Otis Redding. Its position was greatly improved by its distribution deal with Stax Records. In 1967, Atlantic Records became a wholly owned subsidiary of Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, now the Warner Music Group, and expanded into rock and pop music with releases by bands such as Led Zeppelin and Yes.

Atlantic Records is an American major record label founded in October 1947 by Ahmet Ertegün and Herb Abramson. Over its first 20 years of operation, Atlantic Records earned a reputation as one of the most important American recording labels, specializing in jazz, R&B and soul recordings by African-American musicians including Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave, Ruth Brown and Otis Redding. Its position was greatly improved by its distribution deal with Stax Records. In 1967, Atlantic Records became a wholly owned subsidiary of Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, now the Warner Music Group, and expanded into rock and pop music with releases by bands such as Led Zeppelin and Yes.

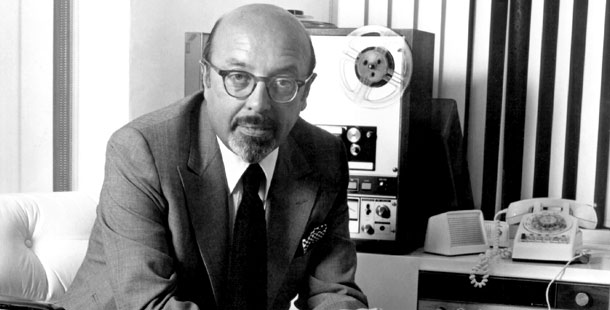

Ahmet Ertegun (1923-2006)

Ahmet Ertegun was a Turkish-American businessman, songwriter and philanthropist.

Ertegun was best known as the co-founder and president of Atlantic Records and for discovering and championing many leading rhythm and blues and rock musicians. He also wrote classic blues and pop songs. In addition he served as the chairman of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and museum, located in Cleveland, Ohio. Ertegun has been described as “one of the most significant figures in the modern recording industry.” In 2017 he was inducted into Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame in recognition of his work in the music business.

In 1944, brothers Nesuhi and Ahmet Ertegun decided to remain in the United States when their mother and sister returned to Turkey after the death of their father Munir Ertegun, Turkey’s first ambassador to the United States. The brothers had become ardent fans of jazz and rhythm & blues music, amassing a collection of over 15,000 78 RPM records. Ahmet ostensibly stayed on in Washington to undertake post-graduate music studies at Georgetown University but immersed himself in the Washington music scene and decided to enter the record business, which was enjoying a resurgence after wartime restrictions on the shellac used in manufacture. He convinced the family dentist, Dr. Vahdi Sabit, to invest $10,000 and recruited Herb Abramson, a dentistry student.

Abramson had worked as a part-time A&R manager/producer for the jazz label National Records, signing Big Joe Turner and Billy Eckstine. He founded Jubilee Records in 1946, but had no interest in its most successful artists. So, in September 1947, he sold his share in Jubilee to his partner, Jerry Blaine, and invested $2,500 in the new Atlantic label.

Atlantic Records was incorporated in October 1947 and was run by Abramson (the company president) and Ertegun (vice-president in charge of A&R, production and promotion). Abramson’s wife Miriam ran the label’s publishing company, Progressive Music, and did most office duties until 1949 when Atlantic hired its first employee, bookkeeper Francine Wakschal, who remained with the label for the next 49 years. Miriam quickly gained a reputation for toughness: staff engineer Tom Dowd later recalled; “Tokyo Rose was the kindest name some people had for her” and Doc Pomus described her as “an extraordinarily vitriolic woman”. When interviewed in 2009, she attributed her reputation to the company’s chronic cash-flow shortage: “… most of the problems we had with artists were that they wanted advances, and that was very difficult for us … we were undercapitalized for a long time.” The label’s original office in the Ritz Hotel in Manhattan proved too expensive so they moved to an $85-per-month room in the Hotel Jefferson. In the early fifties, Atlantic moved from the Hotel Jefferson to offices at 301 West 54th St and then to its best-known home at 356 West 56th St.

Atlantic Records’s first batch of recordings were issued in late January 1948, and included Tiny Grimes’ “That Old Black Magic” and “The Spider” by Joe Morris. In its early years, Atlantic focused principally on modern jazz although it released some country and western and spoken word recordings. Abramson also produced “Magic Records”: children’s records with four grooves on each side, each groove containing a different story, so the story played would be determined by the groove in which the stylus chanced to land.

Soon after its formation, Atlantic faced a serious challenge. In late 1947, James Petrillo, head of the American Federation of Musicians, announced an indefinite ban on all recording activities by union musicians, and this came into force on January 1, 1948. The union action forced Atlantic to use almost all its capital to cut and stockpile enough recordings to last through the ban, which was initially expected to continue for at least a year.

Ertegun and Abramson spent much of the late 1940s and early 1950s scouring nightclubs in search of talent. Ertegun composed many songs under the alias “A. Nugetre”, including Big Joe Turner’s hit “Chains of Love”, working them out in his head and then recording them in 25c recording booths in Times Square and giving the recording to an arranger or straight to the session musicians. Early releases featured Joe Morris, Frank Culley, Art Pepper, Shelly Manne, Pete Rugolo, Tiny Grimes, The Delta Rhythm Boys, The Clovers, The Cardinals, Big Joe Turner, Erroll Garner, Mal Waldron, Howard McGhee, James Moody, Dizzy Gillespie, Jackie & Roy, Sarah Vaughan, Lead Belly, Sonny Terry, Professor Longhair, Mabel Mercer, Sylvia Syms, Billy Taylor, Mary Lou Williams, Sidney Bechet, Django Reinhardt, Earl Hines, Barney Bigard, Pee Wee Russell, Al Hibbler, Meade Lux Lewis, Jimmy Yancey, Johnny Hodges, and Bobby Short.

The hits begin

In early 1949, a New Orleans distributor phoned Ertegun trying to obtain Stick McGhee’s “Drinking Wine, Spo-Dee-O-Dee”, which was unavailable due to the closure of McGhee’s previous label. Ertegun knew Stick’s younger brother Brownie McGhee, with whom Stick happened to be staying, so he contacted the McGhee brothers and cut a re-recording. When released in February 1949, it became Atlantic’s first hit, selling 400,000 copies, and ultimately reached #2 after spending almost half a year in the Billboard R&B charts – although McGhee himself earned just $10 for the session. From this point Atlantic’s fortunes rose rapidly: they recorded 187 songs in 1949 (more than three times the output of the previous two years) and received overtures of a manufacturing and distribution deal with Columbia Records, who would pay Atlantic a 3% royalty on every copy sold. Ertegun asked about artists’ royalties, which he paid, which surprised Columbia executives, who did not, which scuttled the deal.

On the recommendation of broadcaster Willis Conover, Ertegun and Abramson went to see Ruth Brown at the Crystal Caverns club in Washington and invited her to audition for Atlantic. She was badly injured in a car accident en route to New York but Atlantic supported her for nine months and then signed her. Her first release for the label “So Long”, cut at her second Atlantic session on May 25, 1949 with the Eddie Condon band, was a major hit, reaching #6 on the R&B chart. Brown went on to record more than eighty songs for the label, becoming the most prolific and best-selling Atlantic artist of the period. So significant was Brown’s success to Atlantic’s fortunes that the label became known colloquially as “The House That Ruth Built”.

Joe Morris, one of the label’s earliest signings, scored a major hit with his October 1950 release “Anytime, Anyplace, Anywhere”, the first Atlantic record issued in 45rpm format, which the company began pressing in January 1951. The Clovers’ “Don’t You Know I Love You” (composed by Ertegun) became the label’s first R&B #1 in September 1951 and a few weeks later Ruth Brown’s “Teardrops from my Eyes” became its first million-selling record. She hit #1 again in March–April 1952 with “5-10-15 Hours”. “Daddy Daddy” reached #3 in September 1952, and “Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean” (which featured the MJQ’s Connie Kay on drums) reached #1 in February–March 1953, becoming a solid seller for years afterwards, as did the late 1954 “Oh What A Dream”, her last hit with Atlantic. After she left the label in 1961 Brown’s fortunes declined rapidly – within a few years was reduced to working as a cleaner and bus-driver to support her children. In the 1980s she sued her former label for unpaid royalties; although Atlantic, which had prided itself on treating artists fairly, had stopped paying royalties to some artists, Ahmet Ertegun denied this was intentional. Brown eventually received a voluntary payment of $20,000 and founded a charity, the Rhythm and Blues Foundation, in 1988, established with a donation of $1.5 million from Ertegun.

In 1952 Atlantic signed Ray Charles, who scored a string of hugely influential hits including “I Got A Woman”, “What’d I Say” and “Hallelujah I Love Her So”. Later that year The Clovers’ “One Mint Julep” reached #2. In 1953, after learning that singer Clyde McPhatter had been fired from Billy Ward and His Dominoes and was forming his own group (The Drifters), Ahmet Ertegun tracked McPhatter down and signed the new group immediately. Their single “Money Honey” became the biggest R&B hit of the year. Their subsequent records created some controversy: the suggestive “Such A Night” was banned by radio station WXYZ in Detroit and the follow-up “Honey Love” was banned in Memphis though both records reached #1 on the Billboard R&B chart.

Although not a major success in chart terms, female vocal trio The Cookies became an important part of the Atlantic ‘family’. The original group, put together by Atlantic producer Jesse Stone in 1954, comprised Darlene (Ethel) McCrea, Dorothy Jones and Dorothy’s cousin Beulah Robertson, who was replaced in 1956 by Marjorie “Margie” Hendricks. They recorded “In Paradise”, a minor R&B hit in early 1956, but after another unsuccessful release the trio became the regular backing singers for Atlantic recording sessions. They performed on many hits in this period including Joe Turner’s “Corinna, Corinna” and “Lipstick, Powder and Paint”, Chuck Willis’ “It’s Too Late”, and Ray Charles’ “Lonely Avenue”, “Drown In My Own Tears” and “Night Time is the Right Time” (which features Margie Hendricks prominently), before being taken on by Ray Charles and renamed The Raelettes.

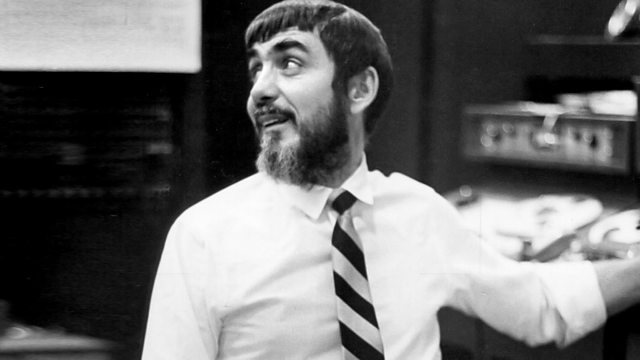

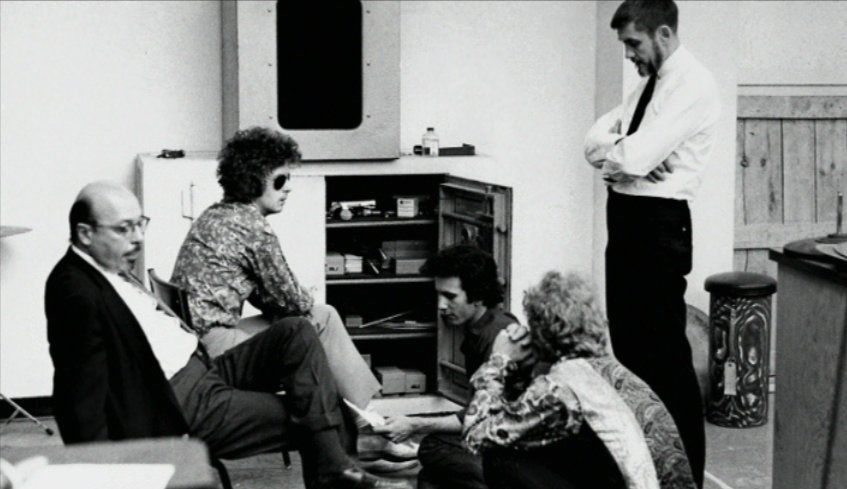

Tom Dowd (1925-2002)

Recording engineer and producer Tom Dowd played a crucial role in Atlantic’s success. He initially worked for Atlantic on a freelance basis, but within a few years he had been hired as the label’s full-time staff engineer. His recordings for Atlantic and Stax exerted a major influence on the history of popular music and he scored more hits than George Martin and Phil Spector combined. As Atlantic’s studio engineer Tom Dowd oversaw many advances in production.

Atlantic was one of the first independent labels to make recordings in stereo: Dowd used a portable stereo recorder which ran simultaneously with the studio’s existing mono recorder. In 1953 (according to Billboard) Atlantic was the first label to issue commercial LPs recorded in the early, experimental stereo system called binaural recording. In this system, recordings were made using two microphones, spaced at approximately the distance between the human ears, and the left and right channels were cut as two separate, parallel grooves, although playing them back required a player with a special tone-arm fitted with dual needles; it was not until around 1958 that the single stylus microgroove system (in which the two stereo channels were cut into either side of a single groove) became the industry standard. By the late 1950s stereo LPs and record players were being introduced into the marketplace. Atlantic’s early stereo recordings included “Lover’s Question” by Clyde McPhatter, “What Am I Living For” by Chuck Willis, “I Cried a Tear” by LaVern Baker, “Splish Splash” by Bobby Darin, “Yakety Yak” by the Coasters and “What’d I Say” by Ray Charles. Although these were primarily 45rpm mono singles for much of the 1950s Dowd stockpiled his “parallel” stereo takes for future release

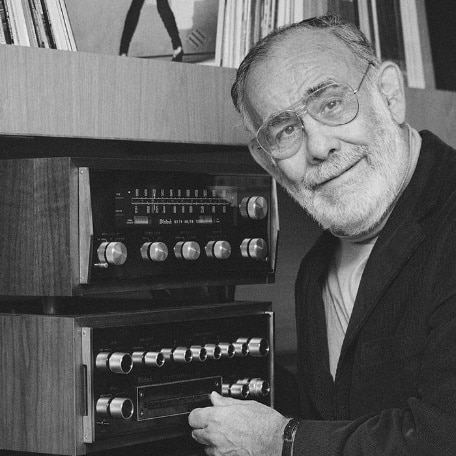

Jerry Wexler (1917-2008)

A music journalist-turned music producer, and was one of the main record industry players behind music from the 1950s through the 1980s. He coined the term “rhythm and blues”, and was integral in signing and/or producing many of the biggest acts of the time, including Ray Charles, the Allman Brothers, Chris Connor, Aretha Franklin, Led Zeppelin, Wilson Pickett, Dire Straits, Dusty Springfield and Bob Dylan.

A music journalist-turned music producer, and was one of the main record industry players behind music from the 1950s through the 1980s. He coined the term “rhythm and blues”, and was integral in signing and/or producing many of the biggest acts of the time, including Ray Charles, the Allman Brothers, Chris Connor, Aretha Franklin, Led Zeppelin, Wilson Pickett, Dire Straits, Dusty Springfield and Bob Dylan.

Wexler was inducted to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987 and in 2017 to the Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.

Herb Abramson was drafted into the US Army in February 1953 and left for Germany where he served in the US Army Dental Corps, although he retained his post as President of Atlantic on full pay. Ertegun recruited Billboard reporter Jerry Wexler in June 1953: who is credited with coining the term “rhythm & blues” to replace the earlier “race music”. He was appointed vice-president and purchased 13% of the company’s stock for $2,063.25. Wexler and Ertegun soon formed a close partnership which, in collaboration with Tom Dowd, produced thirty R&B hits.

Ertegun and Wexler realized many R&B recordings by black artists were being covered by white performers, often with greater chart success: Atlantic’s LaVern Baker had a #4 R&B hit with “Tweedlee Dee” but a rival version by Georgia Gibbs went to #2 on the pop charts, Big Joe Turner’s April 1954 release “Shake, Rattle and Roll” was a #1 R&B hit but only made #22 on the pop chart while Bill Haley & His Comets’s version reached #7, sold over 1 million copies and was Decca Records’ biggest-selling song of the year. In July 1954, as rock’n’roll gathered momentum, Wexler and Ertegun wrote a prescient article for Cash Box, headlined “The Latest Trend: R&B Disks Are Going Pop”, devoted to what they called “cat music”; the same month, Atlantic scored its first major “crossover” hit on the Billboard pop chart when the “Sh-Boom” by The Chords reached #5 (although The Crew-Cuts’ version went to #1). Atlantic missed an important signing in 1955 when Sun Records’ owner Sam Phillips sold Elvis Presley’s recording contract in a bidding war between labels. Atlantic offered $25,000 which, Ertegun later noted, “was all the money we had then.” but they were outbid by RCA Records’s offer of $45,000. In 1990 Ertegun remarked: “The president of RCA at the time had been extensively quoted in Variety damning R&B music as immoral. He soon stopped when RCA signed Elvis Presley.”

Ertegun and Wexler realized many R&B recordings by black artists were being covered by white performers, often with greater chart success: Atlantic’s LaVern Baker had a #4 R&B hit with “Tweedlee Dee” but a rival version by Georgia Gibbs went to #2 on the pop charts, Big Joe Turner’s April 1954 release “Shake, Rattle and Roll” was a #1 R&B hit but only made #22 on the pop chart while Bill Haley & His Comets’s version reached #7, sold over 1 million copies and was Decca Records’ biggest-selling song of the year. In July 1954, as rock’n’roll gathered momentum, Wexler and Ertegun wrote a prescient article for Cash Box, headlined “The Latest Trend: R&B Disks Are Going Pop”, devoted to what they called “cat music”; the same month, Atlantic scored its first major “crossover” hit on the Billboard pop chart when the “Sh-Boom” by The Chords reached #5 (although The Crew-Cuts’ version went to #1). Atlantic missed an important signing in 1955 when Sun Records’ owner Sam Phillips sold Elvis Presley’s recording contract in a bidding war between labels. Atlantic offered $25,000 which, Ertegun later noted, “was all the money we had then.” but they were outbid by RCA Records’s offer of $45,000. In 1990 Ertegun remarked: “The president of RCA at the time had been extensively quoted in Variety damning R&B music as immoral. He soon stopped when RCA signed Elvis Presley.”

Nesuhi Ertegun (1917-1989)

was a Turkish-American record producer and executive of Atlantic Records and WEA International.

Ahmet’s older brother Nesuhi was recruited to the label in January 1955. He had been living in Los Angeles for several years and had only irregular contact with his younger brother, but when Ahmet learned that Nesuhi had been offered a partnership in Atlantic’s rival Imperial Records, he and Wexler convinced Nesuhi to join Atlantic instead. Nesuhi headed the label’s jazz division and built a strong roster, signing West Coast jazzers Shorty Rogers, Jimmy Giuffre, Herbie Mann and Les McCann, as well as Charles Mingus, John Coltrane and the Modern Jazz Quartet, who became a mainstay of the label, releasing twenty albums; by 1958 Atlantic was America’s second-largest independent jazz label. Nesuhi was also in charge of LP album production, a market that was beginning to take off, and he was credited with greatly improving the packaging, production and originality of Atlantic’s LP line

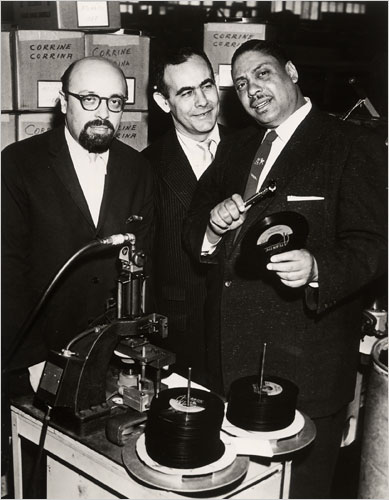

Herb Abramson (1916-1999)

An American record company executive, record producer, and co-founder of Atlantic Records.

Abramson was born in 1916 to a Jewish family in Brooklyn. He studied to be a dentist but got a job with National Records producing Clyde McPhatter, The Ravens, Billy Eckstine, and Big Joe Turner. He founded Jubilee Records in 1946 with Jerry Blaine, intending to record jazz, R&B, and gospel music. Blaine was having some success recording Jewish novelty songs, but this genre did not interest Abramson, so he sold his interest in Jubilee to Blaine. Abramson and his wife Miriam were close friends with jazz fan Ahmet Ertegun, who recognized Abramson’s talent. He approached Abramson with a label proposal, and they founded Atlantic Records in 1947, with Abramson president and Ertegun vice president. Both handled the creative end of the business, and Miriam handled the economics.

Abramson was born in 1916 to a Jewish family in Brooklyn. He studied to be a dentist but got a job with National Records producing Clyde McPhatter, The Ravens, Billy Eckstine, and Big Joe Turner. He founded Jubilee Records in 1946 with Jerry Blaine, intending to record jazz, R&B, and gospel music. Blaine was having some success recording Jewish novelty songs, but this genre did not interest Abramson, so he sold his interest in Jubilee to Blaine. Abramson and his wife Miriam were close friends with jazz fan Ahmet Ertegun, who recognized Abramson’s talent. He approached Abramson with a label proposal, and they founded Atlantic Records in 1947, with Abramson president and Ertegun vice president. Both handled the creative end of the business, and Miriam handled the economics.

In 1953 Abramson was drafted. Jerry Wexler filled in and joined Atlantic as a partner, though Abramson retained the title of president. When Abramson returned from the Army in 1955, he found Atlantic a changed company. Ertegun’s brother, Nesuhi, joined Atlantic in 1955 as a partner and was enjoying great success in selling jazz albums. Ertegun and Wexler were recording R&B hits which crossed over into pop. His failing marriage to Miriam would end in divorce. Abramson returned home from Germany with a pregnant girlfriend who became his second wife.

Ahmet Ertegun and Abramson formed Atco Records in 1955 as a division of Atlantic. Abramson ran the label on his own. He found success with The Coasters but was unable to get a hit with Bobby Darin. When he announced that he was dropping Darin from the label, Ertegun recorded three tracks with Darin and two of them turned into hits: “Queen of the Hop” and “Splish Splash”. Abramson left Atlantic Records in December 1958, selling his stake in the company to ex-wife Miriam Bienstock, (who married music publisher Freddy Bienstock) and Nesuhi Ertegun. Ahmet Ertegun became president of the company. Abramson would start new record labels including Triumph, Blaze, and Festival. His most successful post-Atlantic recording was producing Hi-Heel Sneakers by Tommy Tucker (released on Checker Records) still able to compete in the industry as an independent label.

Abramson developed a method of cutting concentric grooves for a record, so a different recording could be heard depending on which groove the tonearm landed on. That process was used on a series of “Magic Records” Abramson produced which were marketed for children. After leaving Atlantic, Abramson sold the patent to Mattel which used the process to develop the Chatty Cathy talking doll.

Abramson set up his own recording studio in the early 1960s, A-1 Sound Studios (Atlantic-1) at 234 West 56th Street in Manhattan. With engineer Jim Reeves he produced Sidney Barnes, Don Covay, the Darling Sisters, John Davidson, Luther Dixon, J. J. Jackson, Linda and the Vistas, Mr. Wiggles, Johnny Nash, Pigmeat Markum, Ruby & the Romantics, Eddie Singleton, The Supremes, Titus Turner, and the Thymes. He moved A-1 Sound to 76th Street on the ground floor of a hotel off Broadway. Musicians who recorded demos in the studio include Richie Cordell, Hank Crawford, Barry Manilow, Bette Midler, James Moody, Patti Smith, and Muddy Waters. The Godz recorded their first 3 albums at the West 56th Street studio in 1966, 1967 and 1968, and their 4th album at 76th Street in 1973. Jim McCarthy from The Godz also recorded his solo album (Alien) at the 76th Street studio in 1973. Jonathan Thayer, later of Vanguard Recording Studios, engineered for Abramson, as did Rob Fraboni and maintenance engineer Mike Edl, who replaced Carl Lindgren in April 1969. A-1 Sound was managed by his third wife, Barbara, who was with him to the end. He died in Henderson, Nevada, in 1999, seven days before his 83rd birthday.

Rhythm and Blues

Atlantic played a major role in popularizing the new genre that Jerry Wexler dubbed rhythm & blues and it profited handsomely from this. The market for these records exploded during late 1953 and early 1954, as more and more R&B hits crossed over to the mainstream (white) audience. In its tenth anniversary feature on Atlantic, Billboard noted that, “… a very big r&b record might achieve 250,000 sales, but from this point on (1953–54), the industry began to see million sellers, one after the other, in the r&b field”. It observed that the label’s “fresh sound” and the quality of its recordings, arrangements and musicians was a great advance on what was the standard for R&B records at the time, and that for the past five years Atlantic had “dominated the rhythm and blues chart with its roster of powerhouse artists.

Atco Records

A new subsidiary label, Atco Records, was established in 1955 as an effort to keep Abramson involved.

A new subsidiary label, Atco Records, was established in 1955 as an effort to keep Abramson involved.

East West was founded in September 1957; it initially concentrated on singles and featured an “across the board” roster of pop, rock & roll, rhythm & blues and rockabilly artists and its first releases were by Jay Holliday,

Johnny Houston and The Glowtones. After a slow start, Atco had considerable success with The Coasters and Bobby Darin.

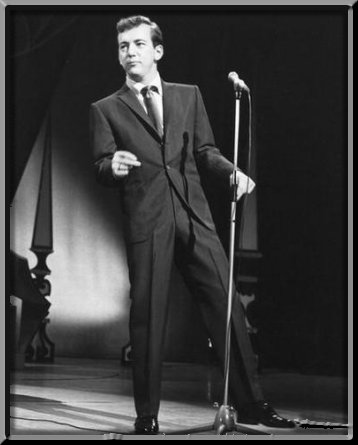

Darin’s early releases had not been successful and Abramson planned to drop him, but Ertegun offered him  another chance, and the session he produced yielded “Splish Splash”, which Darin had written in 12 minutes and which sold 100,000 copies in the first month and became a million-seller. During 1958–59 Darin’s “Queen of the Hop” made the Top 10 on both the US pop and R&B charts and also charted in the UK, “Dream Lover”, a multi-million seller, reached #2 in the US and became a UK #1, and “Mack the Knife” (August 1959) went to #1 in both the US and the UK, sold over 2 million copies and won the 1960 Grammy Award for ‘Record of the Year’. “Beyond the Sea”, an English-language version of the Charles Trenet hit “La Mer”, became his fourth consecutive US/UK Top 10 hit. Darin later signed with Capitol Records and left for Hollywood to begin a movie career although Atco continued to score hits into 1962 with tracks already in the can, including “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby” and “Things”. Darin returned to Atlantic in 1965.

another chance, and the session he produced yielded “Splish Splash”, which Darin had written in 12 minutes and which sold 100,000 copies in the first month and became a million-seller. During 1958–59 Darin’s “Queen of the Hop” made the Top 10 on both the US pop and R&B charts and also charted in the UK, “Dream Lover”, a multi-million seller, reached #2 in the US and became a UK #1, and “Mack the Knife” (August 1959) went to #1 in both the US and the UK, sold over 2 million copies and won the 1960 Grammy Award for ‘Record of the Year’. “Beyond the Sea”, an English-language version of the Charles Trenet hit “La Mer”, became his fourth consecutive US/UK Top 10 hit. Darin later signed with Capitol Records and left for Hollywood to begin a movie career although Atco continued to score hits into 1962 with tracks already in the can, including “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby” and “Things”. Darin returned to Atlantic in 1965.

By 1958, the label had expanded considerably – in 1956 Atlantic’s head office moved to 157 West 57th St, while retaining two floors in the earlier premises at 234 West 56th St. New staff hired between 1956 and 1958 included Gary Kramer (director of publicity and advertising), Lester Lees (national sales manager), Victor Selsman (DJ promotions), Lester Sill (West Coast promotions) and Bob Bushnell (recording engineer).

By 1958, the label had expanded considerably – in 1956 Atlantic’s head office moved to 157 West 57th St, while retaining two floors in the earlier premises at 234 West 56th St. New staff hired between 1956 and 1958 included Gary Kramer (director of publicity and advertising), Lester Lees (national sales manager), Victor Selsman (DJ promotions), Lester Sill (West Coast promotions) and Bob Bushnell (recording engineer).

During the 1960s Atlantic distributed selected titles recorded by many small regional independent labels including Dial (Joe Tex), Karen (The Capitols’ “Cool Jerk”), Rosemart (Don Covay’s “Mercy, Mercy”), Nola (Willie Tee’s “Teasin’ You”), Vault, Class, Shirley, Tomorrow, Instant, Dade (“Mashed Potatoes” by Nat Kendrick & The Swans), Moonglow, Correct-Tone Records, Lu-Pine, Keetch, Royo, T-Neck, Heidi, Sims and others, using those labels’ imprints and separate catalog numbers.

Leiber, Stoller and Spector

In October 1955, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller scored a West Coast hit with Los Angeles-based vocal group The Robins, who released “Smokey Joe’s Cafe” on the duo’s own Spark Records label. Seeking a national outlet, they leased the master to Atco and in November Atlantic purchased Spark and its catalog; Leiber and Stoller signed a landmark deal with Atlantic that made them America’s first independent record producers. In 1956 two members of The Robins, Carl Gardner and Bobby Nunn, formed The Coasters who finally provided Atlantic with the crossover success it had been striving for. Their first (March 1956) Atco release (recorded in Hollywood) was “Down in Mexico”, a Top 10 R&B hit: the double-sided “Young Blood”/”Searchin'” (also recorded in Hollywood) followed, with both sides entering the pop Top 10 after radio exposure and both charting for over 20 weeks – “Searchin'” reached #3 and “Young Blood” #8. Following Leiber and Stoller to New York, The Coasters’ then cut “Yakety Yak” (June 1958), featuring the saxophone of King Curtis, and this became Atlantic’s first pop #1; “Charlie Brown” made #2 on both the pop and R&B charts in February 1959, “Along Came Jones” also reached the pop Top 10 as did “Poison Ivy” (#7, Aug. 1959). “Little Egypt” (1961) was their last hit, reaching #21 in the pop chart.

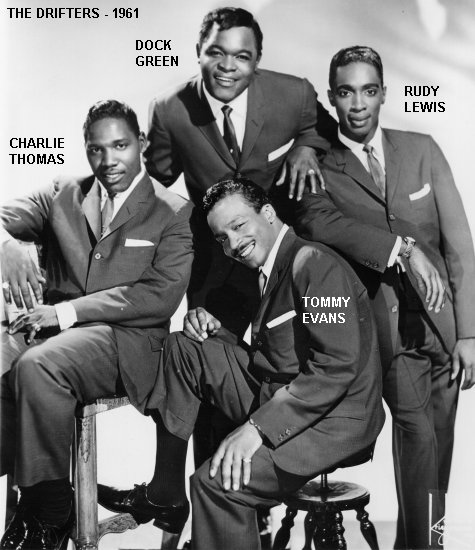

Leiber and Stoller also wrote the classic “Ruby Baby” for The Drifters, a 1956 #13 R&B hit that featured Johnny Moore as lead vocalist (replacing Clyde McPhatter, who had been drafted); it became a pop standard and reached #2 in 1962 when re-recorded by Dion. By 1958, The Drifters had undergone many lineup changes and their former popularity was waning.

That May, after one of the members got into a fight with the manager of the Apollo Theater, group manager George Treadwell sacked the entire lineup and recruited the members of The Five Crowns to become the ‘new’ Drifters. Leiber and Stoller produced “There Goes My Baby” with this second incarnation, featuring a lead vocal by Ben E. King, who also co-wrote the song. It was the first R&B song to feature a string arrangement, but Ertegun disliked it and Jerry Wexler was appalled, reportedly telling the producers; “Get that out of here. I hate it. It’s out of tune and it’s phony and it’s shit and get it out of here”. They refused to release it for several months, but when they finally relented and released it as a single in April 1959, the song shot to #1.

Phil Spector had learned the basics of record production working for Lester Sill and Lee Hazlewood’s Trey Records label (which was distributed by Atlantic) in California in the late 1950s. At Sill’s recommendation, he returned to New York to work for Leiber and Stoller in early 1960. Leiber and Stoller assigned him to produce Ray Peterson’s “Corrine, Corrina” and Curtis Lee’s “Pretty Little Angel Eyes” (released on Peterson’s Dunes Records label), both of which became hits. As a result, Atlantic signed him as a staff producer, though his difficult personality was already evident, and Ahmet Ertegun was reportedly the only Atlantic executive who liked him. Leiber later remarked, “He wasn’t likeable. He was funny, he was amusing – but he wasn’t nice.” Wexler reportedly had no time for him and Miriam Bienstock, in her typically blunt fashion, described Spector’s erratic behavior “insane” and considered him “a pain in the neck”. When Ertegun took Spector to meet Bobby Darin, he openly criticized Darin’s songwriting, with the result that Darin had him thrown out of the house.

Despite these issues, Atlantic kept Spector on for a time, but with diminishing returns. Spector produced The Top Notes’ original version of “Twist and Shout”, but it flopped. Bert Berns, the song’s writer, was incensed by Spector’s arrangement, which he believed had ruined the song, so Berns re-recorded it the way he thought it should sound with The Isley Brothers, and it became a huge hit. Spector also produced Jean DuShon, Billy Storm, LaVern Baker and Ruth Brown during his short stay at Atlantic, with only moderate success. He left Atlantic in 1961 and returned to Los Angeles, where he founded Philles Records with Lester Sill and soon established himself as the preeminent American pop producer of the mid-1960s.

In early 1960 the Drifters came out with “Dance With Me”, which reached #15 on the pop chart and #2 R&B. “This Magic Moment” reached #16 on the pop chart, and their classic rendition of Doc Pomus’ poignant “Save The Last Dance For Me” became a major international pop hit, reaching #1 in the US and #2 in the UK. However, in May 1960, after only one year and just 10 recordings with the Drifters, lead singer Benjamin Nelson left the group due to a dispute with manager George Treadwell. Assuming the stage name Ben E. King, he launched a successful solo career, although the Drifters went on to score several more big hits.

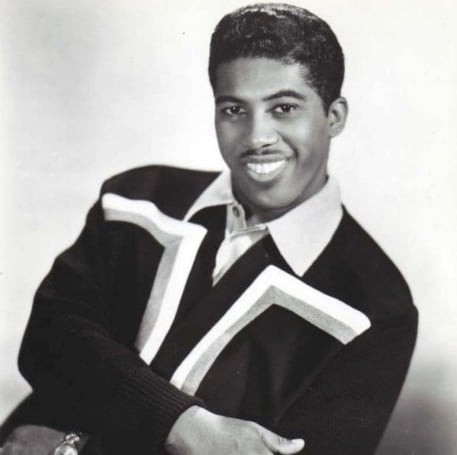

King’s first solo single, “Spanish Harlem” (co-written by Leiber and Spector and produced by Leiber and Stoller), became a Top 10 pop hit in early 1961. It was followed by “Stand By Me”, a re-interpretation of the gospel standard “Lord, Stand By Me”, with new lyrics by King and orchestration by Stan Applebaum. Reaching #4 on the pop chart, the song quickly became a standard covered by many artists including John Lennon. It has since been included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s 500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll listing and in 2001 it was voted #25 in the ‘Songs of the Century’ poll conducted by the Recording Industry Association of America. In late 1962, The Drifters returned to the charts, fronted by new lead vocalist Rudy Lewis, performing hits recorded with Ben E. King on stage and TV. “Up On The Roof”, co-written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, was another major crossover hit making the Top 5 on both the pop and R&B charts, and Mann, Weil, Leiber, and Stoller’s “On Broadway” made the Top 10 on both charts. It has since been covered by many artists. The Drifters’ last hit, “Under The Boardwalk” (1964), was produced by Bert Berns and orchestrated by British arranger-producer-composer Mike Leander. Lead singer Rudy Lewis was found dead on the morning of the recording session (May 21, 1964) and former lead singer Johnny Moore was brought in to replace him. Despite this tragedy, the song became a big hit, reaching #4 on the pop chart and #1 on the R&B chart, and went on to be covered by many other acts, including The Rolling Stones.

King’s first solo single, “Spanish Harlem” (co-written by Leiber and Spector and produced by Leiber and Stoller), became a Top 10 pop hit in early 1961. It was followed by “Stand By Me”, a re-interpretation of the gospel standard “Lord, Stand By Me”, with new lyrics by King and orchestration by Stan Applebaum. Reaching #4 on the pop chart, the song quickly became a standard covered by many artists including John Lennon. It has since been included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s 500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll listing and in 2001 it was voted #25 in the ‘Songs of the Century’ poll conducted by the Recording Industry Association of America. In late 1962, The Drifters returned to the charts, fronted by new lead vocalist Rudy Lewis, performing hits recorded with Ben E. King on stage and TV. “Up On The Roof”, co-written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, was another major crossover hit making the Top 5 on both the pop and R&B charts, and Mann, Weil, Leiber, and Stoller’s “On Broadway” made the Top 10 on both charts. It has since been covered by many artists. The Drifters’ last hit, “Under The Boardwalk” (1964), was produced by Bert Berns and orchestrated by British arranger-producer-composer Mike Leander. Lead singer Rudy Lewis was found dead on the morning of the recording session (May 21, 1964) and former lead singer Johnny Moore was brought in to replace him. Despite this tragedy, the song became a big hit, reaching #4 on the pop chart and #1 on the R&B chart, and went on to be covered by many other acts, including The Rolling Stones.

The Leiber & Stoller/Atlantic partnership was enormously successful, but by 1962 the relationship was deteriorating. The duo reportedly resented the credit accorded to Spector, but their own artistic and financial demands alienated the Atlantic executives. From the beginning, Miriam Bienstock “couldn’t see why it was necessary to use them” and they infuriated Jerry Wexler by asking for producers’ credits on record labels and sleeves, although this was grudgingly granted. The breaking point came when duo asked for a producer’s royalty, which was also granted informally, but their accountant insisted on a written contract and also requested an audit of Atlantic’s accounts. When this was carried out (over Jerry Wexler’s strenuous objections) it was found that Leiber and Stoller had been underpaid by $18,000. Although Leiber considered dropping the matter, Stoller insisted on pressing Atlantic for payment, but when they presented their request, Wexler exploded, telling them it would mean the end of their relationship with Atlantic. Leiber and Stoller backed down but the showdown ended the partnership anyway: Ertegun and Wexler told them they would not be involved in The Drifters’ next recording, giving the assignment to Phil Spector. Atlantic quickly filled the gap left by Leiber and Stoller’s departure with the hiring of producer and songwriter Bert Berns, who had recently scored a major hit with his remake of “Twist and Shout” for The Isley Brothers.

The ramifications of the split continued after Leiber and Stoller left Atlantic: after a period with United Artists Records (where they scored a number of hits), in 1963 they set up Red Bird Records with George Goldner. Although they scored major hits (including The Dixie Cups’ “Chapel of Love” and The Shangri-Las “Leader of the Pack”), the label’s business position was precarious, so in late 1964 they approached Jerry Wexler, proposing a merger with Atlantic. When interviewed in 1990 for Ertegun’s biography, Wexler declined to discuss the matter, but Ertegun himself claimed that these negotiations soon developed into a plan to buy him out. At this time (September 1964), the Ertegun brothers and Wexler were in the process of buying out the company’s other two shareholders, Dr. Sabit and Miriam Bienstock and it was proposed (presumably by Wexler) that Leiber and Stoller would buy Sabit’s shares. Leiber, Stoller, Goldner, and Wexler pitched their plan to Ertegun at a fateful lunch meeting at the Plaza Hotel in New York. Though Leiber and Stoller were adamant it was not their intention to buy Ertegun out, Ahmet was aggravated by Goldner’s high-handed attitude and became convinced that Wexler was conspiring with them. Wexler then told Ertegun that if he refused, Wexler would do the deal without him, but this was impossible since the Ertegun brothers still held the majority share, while Wexler only controlled about 20%. Ertegun nursed a lifelong grudge against Leiber and Stoller and the affair drove an irreparable wedge between Ertegun and Wexler.

Stax

Atlantic was doing so well in early 1959 that some scheduled releases were held back and the company enjoyed two successive months of gross sales of over $1 million that summer, thanks to hits by The Coasters, The Drifters, LaVern Baker, Ray Charles, Bobby Darin and Clyde McPhatter However, only months later the company was reeling from the successive loss of its two biggest artists, Bobby Darin and Ray Charles, who together accounted for one third of sales. Darin, who moved to the Los Angeles area, signed with Capitol Records. Charles signed a deal with ABC-Paramount Records in November 1959 that reportedly included increased royalties, a production deal, profit-sharing and eventual ownership of his master tapes. Wexler later commented; “It was very grim. I thought we were going to die” and Ertegun in 1990 disputed whether Charles had received the promised benefits. It led to a permanent rift between Charles and his former colleagues, although Ertegun remained good friends with Darin who returned to Atlantic in 1966. Charles returned to Atlantic in 1977.

Atlantic was doing so well in early 1959 that some scheduled releases were held back and the company enjoyed two successive months of gross sales of over $1 million that summer, thanks to hits by The Coasters, The Drifters, LaVern Baker, Ray Charles, Bobby Darin and Clyde McPhatter However, only months later the company was reeling from the successive loss of its two biggest artists, Bobby Darin and Ray Charles, who together accounted for one third of sales. Darin, who moved to the Los Angeles area, signed with Capitol Records. Charles signed a deal with ABC-Paramount Records in November 1959 that reportedly included increased royalties, a production deal, profit-sharing and eventual ownership of his master tapes. Wexler later commented; “It was very grim. I thought we were going to die” and Ertegun in 1990 disputed whether Charles had received the promised benefits. It led to a permanent rift between Charles and his former colleagues, although Ertegun remained good friends with Darin who returned to Atlantic in 1966. Charles returned to Atlantic in 1977.

Through 1961–62 Leiber and Stoller’s successes maintained the label’s fortunes, and these were further enhanced by a licensing deal with a small Memphis-based independent label Stax Records, which would soon prove to be of enormous value. In 1960, Atlantic’s Memphis distributor Buster Williams contacted Wexler and told him he was pressing large quantities of “Cause I Love You”, a duet between Memphis-based singers Carla Thomas and her father Rufus Thomas, which was released on a small local label called Satellite (which was soon renamed Stax Records, from the names of the owners, Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton, in 1961). Wexler contacted the co-owner of Satellite, Jim Stewart, who agreed to lease the record to Atlantic for $1000 plus a small royalty (the first money the label had ever made). The deal included a $5000 payment against a five-year option on all other records. When Carla Thomas’ first solo single, “Gee Whiz (Look at his Eyes)” began to attract national attention in 1961 New York producer Hy Weiss, went to Memphis to try to acquire the rights, but after examining the contract he told Wexler it gave Atlantic options on all Satellite recordings for the next five years.

The deal to distribute Satellite’s “Last Night” by The Mar-Keys on the Satellite label marked the first time Atlantic began marketing outside tracks on a non-Atlantic label. When Stewart discovered there was another label in California called Satellite Records, he changed the name of his label to Stax.

Atlantic began pressing and distributing Stax records and Wexler soon sent Tom Dowd to upgrade Stax’s recording equipment and facilities. Wexler was impressed by the easy-going, cooperative atmosphere at the Stax studios and by the distinctive sound of the label’s racially integrated group of ‘house’ musicians (which he described as “an unthinkably great band”) and he was soon bringing Atlantic artists to Memphis to record. Shortly afterwards Stewart and Wexler hired Al Bell, then working as a DJ at a Washington DC radio station, to take over national promotion of Stax releases, the first African-American partner in the label.

In 1962 the Stax deal began to reap major rewards for both labels. An after-hours jam by members of the Stax house band resulted in the classic instrumental “Green Onions”. The single was issued nationally in August 1962, by which time the band had been dubbed Booker T & the MGs; “Green Onions” became the biggest instrumental hit of the year, reaching #1 on the R&B chart and #3 on the pop chart, where it stayed for 16 weeks, and it sold over one million copies, earning a gold record award.

1962 also saw the Stax debut of Otis Redding, who had been Johnny Jenkins’ driver and was allowed to record several songs at the end of one of Jenkins’ sessions, among them his own “These Arms of Mine”, which was released on Stax’s Volt subsidiary and became a minor hit in the south. Over the next five years Redding would become one of Stax’s most important artists. During 1965 Redding broke through into the national charts; “Mr. Pitiful” reached #10 on the soul chart and just missed out on the pop Top 40, followed by “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long”, which made #2 on the soul chart and peaked at #21. “Respect” also performed strongly, reaching #4 on the soul chart and #35 on the pop chart. Over the next five years Stax and its subsidiary Volt provided Atlantic with a tremendous run of success, and many Atlantic artists were taken to Memphis to record. Among the many hits recorded by (or at) Stax between 1963 and 1967 were Rufus Thomas’ “Walking The Dog”, Otis Redding’s “Respect”, his classic version of “Try A Little Tenderness” and “Tramp”, his hit duet with Carla Thomas, Eddie Floyd’s “Knock On Wood” and The Bar-Kays’ “Soul Finger”. Sam & Dave were signed to Atlantic but recorded at Stax at Jerry Wexler’s suggestion; with the Stax band and the writing team of Isaac Hayes and David Porter, the duo scored eight consecutive R&B Top 20 hits including “You Don’t Know Like I Know”, “Hold On, I’m Coming”, “When Something Is Wrong With My Baby”, “Soul Man” and “I Thank You; Wilson Pickett scored hits with “In The Midnight Hour”, “634-5789”, “Land of 1000 Dances”, “Mustang Sally”, “Funky Broadway” and “I’m In Love”.

Some of Pickett’s earlier hits were recorded at Stax, but in early 1966 Jim Stewart banned all non-Stax productions from the studio, so Atlantic began using other southern studios, notably Rick Hall’s FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and the American Group Productions studio in Memphis, run by former Stax producer Chips Moman.

The soul years, 1962–1967

In late 1961 singer Solomon Burke arrived at Jerry Wexler’s office unannounced. Wexler was a fan of Burke’s and had long wanted to sign him so when Burke told Wexler his contract with his former label had expired Wexler replied: “You’re home. I’m signing you today”. The first song Wexler produced with Burke was “Just Out of Reach”, which became a big hit in September 1961. The soul/country & western crossover predated Ray Charles’ similar venture by more than 6 months. Burke became a consistent big seller through the mid-1960s and scored hits on Atlantic into 1968. In 1962 folk music was booming and the label came very close to signing Peter, Paul & Mary; although Wexler and Ertegun pursued them vigorously the deal fell through at the last minute and they later discovered music publisher Artie Mogull had introduced their manager Albert Grossman to Warner Bros. Records executive Herman Starr, who had made the trio an irresistible offer that gave them complete creative control over the recording and packaging of their music.

Doris Troy signed with Atlantic in early 1963 and in June scored a major hit with “Just One Look”, which she co-wrote and which reached #3 on the R&B chart and #10 on the pop chart. She scored another UK hit with “What’cha Gonna Do About It” and went on to a long and a successful career as a backing vocalist on many Dusty Springfield hits and with other famous acts including Pink Floyd, George Harrison and Nick Drake. “Just One Look” has been covered by many other artists including The Hollies, whose version became a major hit in the UK and gave the group its first US chart placing in 1964.

1967–68 was a peak period for Atlantic, as the string of hits coming from the Stax roster was augmented by the tremendous crossover success of Aretha Franklin, who shot to fame virtually overnight, becoming the preeminent female soul artist of the era, and earning the title “Queen of Soul”. Franklin signed with Atlantic Records in November 1966 after the expiry of her contract with Columbia Records, who had unsuccessfully tried to market her as a jazz singer. After she signed with Atlantic, a Columbia executive asked Jerry Wexler what he was going to do with Franklin, to which he replied “we’re gonna put her back in church”.Wexler was determined to return Franklin to her gospel roots and personally took over her production at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, crucially allowing her to establish the “feel” of the songs by singing while accompanying herself on piano. Although the session was fraught with tension (mainly due to the fractious presence of Aretha’s then husband and manager, Ted White), it yielded a double-sided hit which initiated a run of seven consecutive singles that made both the US pop and soul Top 10, and of which five were million-sellers; “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You)” (b/w “Do Right Woman”) (soul #1, pop #9), “Respect” (soul and pop #1), “Baby, I Love You” (soul #1, pop #4), “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” (soul #2, pop #8), “Chain of Fools” (soul #1, pop #2), “Since You’ve Been Gone” (1968, soul #1, pop #5) and “Think” (1968, soul #1, pop #7).

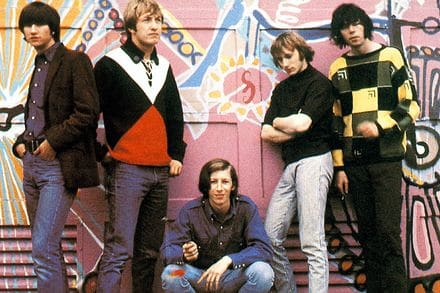

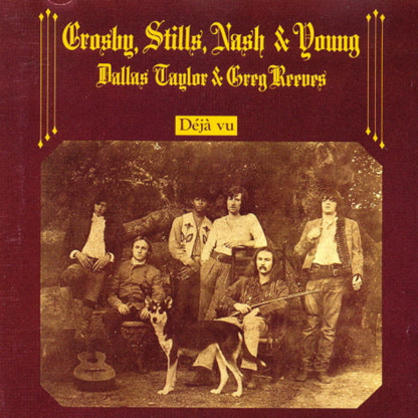

The mid-1960s British Invasion led Atlantic to change its British distributor, since Decca did not give Atlantic access to its British recording artists, who mainly appeared in the US via their US subsidiary London Records. In 1966 Atlantic signed a new reciprocal licensing deal with Polydor Records. Thanks to Polydor’s recent distribution deal with Robert Stigwood’s Reaction label, the deal included newly formed British “supergroup” Cream, whose debut album was released on Atco in late 1966. In May 1967 the group came to Atlantic’s New York studio to record their US breakthrough LP Disraeli Gears with Tom Dowd; it became a Top 5 LP in both the US and the UK, with the single “Sunshine of Your Love” reaching #5 on the Billboard Hot 100. Although Jerry Wexler was dismissive of the new developments in popular music—derisively dubbing the new generation of musicians as “the rockoids” Cream’s American success marked the beginning of Atlantic’s hugely successful diversification into the exploding rock music market, which would reap enormous rewards in the 1970s with signings such as Led Zeppelin, Yes, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and Bad Company.

In late 1966 rising Los Angeles group Buffalo Springfield were signed to the Atco label, and in early 1967 they scored a major US hit with their second single, “For What It’s Worth”, which made the national Top 10, sold over 1 million copies and earned a gold record award.

In late 1966 rising Los Angeles group Buffalo Springfield were signed to the Atco label, and in early 1967 they scored a major US hit with their second single, “For What It’s Worth”, which made the national Top 10, sold over 1 million copies and earned a gold record award.

Despite this early breakthrough and Ahmet Ertegun’s high hopes for the band, internal tensions and the drug-related deportation of Canadian-born bassist Bruce Palmer led to the band splitting up in May 1968 without achieving any further hits.

However former members Stephen Stills and Neil Young would go on to play a major role in Atlantic’s rock success as members of 1970s supergroup Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

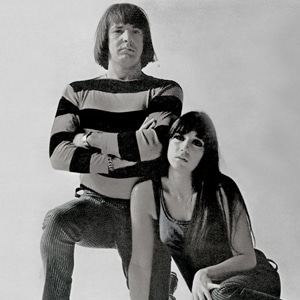

In 1965 Jerry Wexler signed Los Angeles duo Sonny & Cher to Atco and their first single for the label became an international smash hit; “I Got You Babe” spent three weeks at #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and sold more than million copies in the US, as well as reaching #1 in the UK, where it sold 780,000 copies. Over the next three years the duo scored a string of hits, with a total of five Top 20 US singles including the #6 hit “The Beat Goes On” (1967), and their debut album Look At Us reached #2 on the US album chart in 1965.